Exponential Convergence of Gradient Descent with Lipschitz Smoothness and Strong Convexity

A little bit of theory

By Christian | March 19, 2018

So in the world of practical optimization, especially with respect to applications in things like Machine Learning, it is super common to hear about the use of Gradient Descent. Gradient Descent is a simple recursive scheme that is used to finding critical points (hopefully local optima!) of functions. This scheme takes the following form:

\begin{align} x_{k+1} &= x_{k} - \alpha_k \nabla f(x_{k}) \end{align}where $x_k \in \mathbb{R}^n$ is the $k^{th}$ estimate of a critical point for a function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$, $\alpha_k$ is called the stepsize, and $\nabla f(x)$ is the gradient of $f$ at some location $x$. The cool thing about using Gradient Descent is that it is fairly intuitive. Just thinking about the terms in the expression, you can view each improved estimate as taking the current estimate $x_k$ and stepping in the steepest direction from the current estimate, $-\nabla f(x_k)$, for some small distance $\alpha_k$ so that we hopefully get a new estimate $x_{k+1}$ closer to the actual critical point. Seems pretty intuitive to me!

Now it is neat to know we have some recursion we can use to arrive at a critical point, but what we really need to know is how quickly we will converge to such a location because how else will we know if this strategy is useful? To take things further, we might also want to know if we are guaranteed to find a local minima or even global minima.. so some important things to worry about!

In this post, I'm going to walk through a convergence proof for the case where $f(\cdot)$ is strongly convex and is Lipschitz smooth with a Lipschitz constant $C$ that holds everywhere. This proof will highlight an interesting theoretical result when using Gradient Descent for subsets of problems that satisfy the above criteria. So with that, let us get started!

Theoretical Analysis

So the goal in this part of the post is to come up with some theoretical bounds on Gradient Descent that we can use to show convergence to a local minima for some convex function $f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$. To get rolling on that, we should try to use our assumptions on $f$ of strong convexity and Lipschitz smoothness and bring them into a tangible, mathematical form we can use.

For both of the above assumptions, we can relate them to the Hessian of $f$, $\nabla^2 f(x)$, in the following manner:

\begin{align} \nabla^2 f(x) &\succeq c I \tag{Strong Convexity}\\ \nabla^2 f(x) &\preceq C I \tag{Lipschitz Smoothness} \end{align}where the above relationships hold for all $x \in \mathbb{R}^n$. Using Taylor's Theorem and the above expressions, we can also find some convenient bounds on $f(x)$ $\forall x$. These bounds can be found to be the following:

\begin{align} f(x) \geq f(y) + \nabla f(y)^T (x - y) + \frac{c}{2} \norm{x - y}^2 \tag{Strong Convexity}\\ f(x) \leq f(y) + \nabla f(y)^T (x - y) + \frac{C}{2} \norm{x - y}^2 \tag{Lipschitz Smoothness}\\ \end{align}Dope! We have some inequalities that should become quite useful shortly! Now let us assume an optimal location $x^*$ exists that such that $f(x^*) = \inf_{v \in \mathbb{R}^n} f(v)$. We can use this assumption to come up with the following useful inequality:

\begin{align} f(x^*) &= \inf_{v} f(v) \\ &= \inf_{v} f(x_k + v) \\ &\geq \inf_{v} \left(f(x_k) + \nabla f(x_k)^T v + \frac{c}{2} \norm{v}^2 \right) \\ &= f(x_k) - \frac{1}{2c} \norm{\nabla f(x_k)}^2 \tag{$\dagger$} \end{align}Using the definition of Gradient Descent, Lipschitz smoothness, and the choice of $\alpha_k = \frac{1}{C}$, we can obtain the other useful inequality:

\begin{align*} f(x_k) &\leq f(x_{k-1}) + \nabla f(x_{k-1})^T \left(x_{k} - x_{k-1}\right) + \frac{C}{2} \norm{x_{k} - x_{k-1}}^2 \\ &= f(x_{k-1}) - \frac{1}{C}\nabla f(x_{k-1})^T \nabla f(x_{k-1}) + \frac{C}{2} \norm{\frac{1}{C} \nabla f(x_{k-1})}^2 \\ &= f(x_{k-1}) - \frac{1}{2C} \norm{\nabla f(x_{k-1})}^2 \tag{$\ddagger$} \end{align*}Using both $(\dagger)$ and $(\ddagger)$, we can get close to our ultimate goal. We can make progress using the following steps:

\begin{align*} f(x_k) &\leq f(x_{k-1}) - \frac{1}{2C} \norm{\nabla f(x_{k-1})}^2 \\ &\leq f(x_{k-1}) + \frac{c}{C}\left(f(x^*) - f(x_{k-1})\right) \\ &= \left(1 - r \right) f(x_{k-1}) + r f(x^*) \\ f(x_k) - f(x^*) &\leq \left(1 - r \right) f(x_{k-1}) - \left(1 - r \right) f(x^*) \\ &= \left(1 - r \right) \left(f(x_{k-1}) - f(x^*)\right) \\ &\leq \left(1 - r \right)^2 \left(f(x_{k-2}) - f(x^*)\right) \\ &\vdots \\ &\leq \left(1 - r \right)^k \left(f(x_{0}) - f(x^*)\right) \\ &\leq K \left(1 - r \right)^k \end{align*}where $K > 0$ is some constant, $r = \frac{c}{C}$, and $0 \lt r \lt 1$. Now we must try to bound $\left(1 - r \right)^k$, which we can do in the following manner:

\begin{align*} (1-r)^k &= \exp\left( \log (1 - r)^k\right) \\ &= \exp\left( k \log (1-r) \right) \\ &= \exp\left( -k \sum_{l=1}^{\infty} \frac{r^l}{l} \right) \\ &\leq \exp\left( -k r \right) \end{align*}Using the above result, we can achieve the final bound to be

\begin{align*} f(x_k) - f(x^*) &\leq K \left(1 - r \right)^k \\ &\leq K \exp\left( -k r \right) \end{align*}Awesome! As we can see, we are able to bound the error between the minimum and our current estimate of the minimum by an exponentially decreasing term as the number of iterations increases! This shows that Gradient Descent, under the assumptions that $f(x)$ is Lipschitz smooth and strongly convex, leads to an exponential convergence to the local minimum. Note that since $f(x)$ is convex, the local minimum is also the global minimum! With that, we have found a pretty intriguing result!

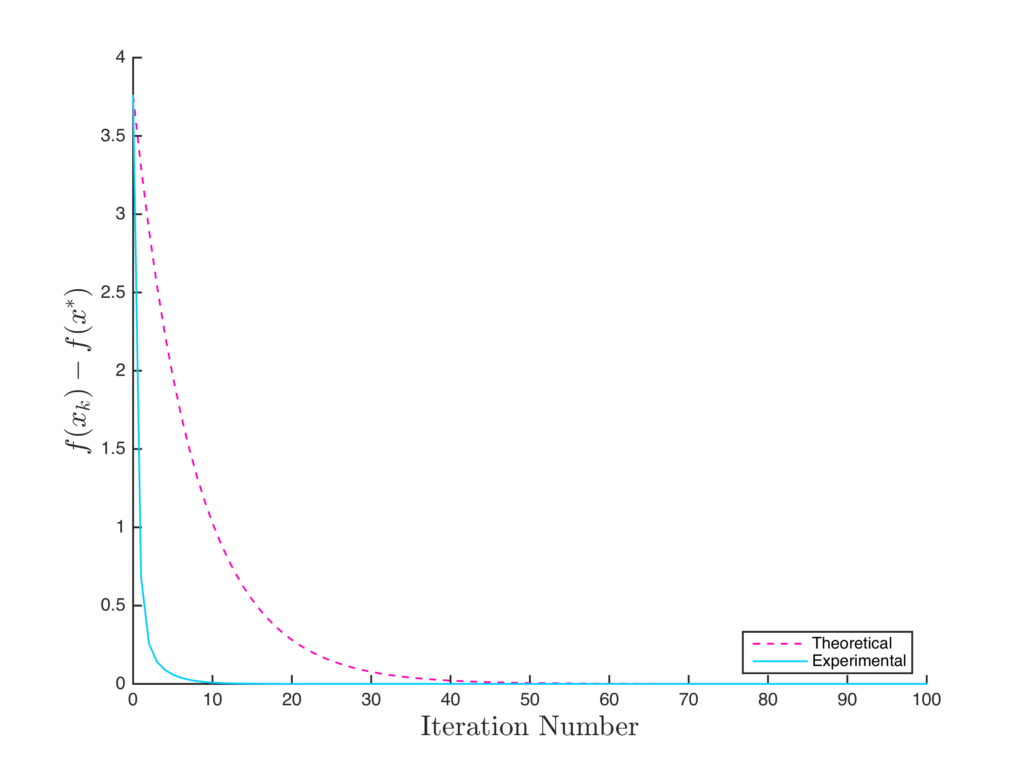

Numerical Study

Just to try and prove this bound makes sense, I put together some basic code to show how the bound compares to the actual convergence. For this problem, I assumed $f(x) = (x - x^{*})^T Q (x - x^{*})$ where $Q$ was positive definite and chose $K$ to be $f(x_0)$ since $f(x^{*}) = 0$. As the figure below shows, the bound certainly overestimates the error and yet still converges exponentially fast!

Conclusion

As we can see in this post, having some extra functions on a function $f(x)$ we would like to minimize can result in some shocking convergence rates and potentially other useful properties! In this instance, we see having a function $f(x)$ that is both Lipschitz smooth and strongly convex results in exponential convergence to the global minimum and we have seen this holds true in a numerical experiment. It's always super cool to see how theory and practice mesh together and looks like in this instance we will be able to use it to better understand how to benefit from Gradient Descent in practice!