Control from Approximate Dynamic Programming Using State-Space Discretization

Recursing through space and time

By Christian | February 04, 2017

In a recent post, principles of Dynamic Programming were used to derive a recursive control algorithm for Deterministic Linear Control systems. The challenges with the approach used in that blog post is that it is only readily useful for Linear Control Systems with linear cost functions. What if, instead, we had a Nonlinear System to control or a cost function with some nonlinear terms? Such a problem would be challenging to solve using the approach described in the former blog post.

In this blog post, we are going to cover a more general approximate Dynamic Programming approach that approximates the optimal controller by essentially discretizing the state space and control space. This approach will be shown to generalize to any nonlinear problems, no matter if the nonlinearity comes from the dynamics or cost function. While this approximate solution scheme is conveniently general in a mathematical sense, the limitations with respect to the Curse of Dimensionality will show why this approach cannot be used for every problem.

The Approximate Dynamic Programming Formulation

Definitions

$\def\bigtimes{\mathop{\vcenter{\huge\times}}}$ To approach approximating these Dynamic Programming problems, we must first start out with an applicable formulation. One of the first steps will be defining various items that will help make the work later more precise and understandable. The first two quantities are that of the complete state space and control space. We can define those two spaces in the following manner:

\begin{align} \mathcal{X} &= \bigtimes_{i=1}^{n} \lbrack x_{l}^{(i)}, x_{u}^{(i)}\rbrack \\ \mathcal{U} &= \bigtimes_{i=1}^{m} \lbrack u_{l}^{(i)}, u_{u}^{(i)}\rbrack \end{align}where $\mathcal{X} \subset \mathbb{R}^{n}$ is the state space, $x_{l}^{(i)}, x_{u}^{(i)}$ are the $i^{th}$ lower and upper bounds of the state space, $\mathcal{U} \subset \mathbb{R}^{m}$ is the control space, and $u_{l}^{(i)}, u_{u}^{(i)}$ are the $i^{th}$ lower and upper bounds of the control space. Now these spaces represent the complete state space and control space. To approximate the Dynamic Programming problem, though, we will instead discretize the state space and control space into subspaces $\mathcal{X}_{D} \subset \mathcal{X}$ and $\mathcal{U}_{D} \subset \mathcal{U}$. We can thus define $\mathcal{X}_{D}$ and $\mathcal{U}_{D}$ in the following manner:

\begin{align} \mathcal{X}_{D} &= \bigtimes_{i=1}^{n} L( x_{l}^{(i)}, x_{u}^{(i)}, N_i ) \label{xd} \\ \mathcal{U}_{D} &= \bigtimes_{i=1}^{m} L( u_{l}^{(i)}, u_{u}^{(i)}, M_i ) \label{ud} \\ L(a,b,N) &= \left \lbrace a + j \Delta : \Delta = \frac{b-a}{N-1}, j \in \lbrace 0, 1, 2, \cdots, N-1 \rbrace \right \rbrace \end{align}What the formulation above shows is we generate a subset of both $\mathcal{X}$ and $\mathcal{U}$ by breaking up the bounds of the $i^{th}$ dimensions into pieces. With these definitions, we can proceed with the mathematical and algorithmic formulation of the problem!

Mathematical Formulation

To make a general (deterministic) control problem applicable to Dynamic Programming, it needs to fit within the following framework:

\begin{align} \boldsymbol{x}_{k+1} &= f(\boldsymbol{x}_{k},\boldsymbol{u}_{k}) \\ % \mu_{k}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j}) &= \arg\min_{\hat{\boldsymbol{u}} \in \mathcal{U}_{D}} g_{k}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j},\hat{\boldsymbol{u}}) + V_{k+1}^{*}(f(\boldsymbol{x}_{j},\hat{\boldsymbol{u}}))\\ % V_{k}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j}) &= g_{k}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j},\mu_{k}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j})) + V_{k+1}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x}_{k+1})\\ % V_{k}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j}) &= g_{k}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j},\mu_{k}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j})) + V_{k+1}^{*}(f(\boldsymbol{x}_{j},\mu_{k}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x}_{j}))) \nonumber \\ % V_{N}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x}_{N}) &= g_{N}(\boldsymbol{x}_{N}) \end{align}$\forall k \in \lbrace 1, 2, 3, \cdots, N-1 \rbrace$, and $\forall j \in \lbrace 1, 2, 3, \cdots, |\mathcal{X}_{D}| \rbrace $. Note as well that $\mu_{k}^{*}(\boldsymbol{x})$ is the optimal controller (or policy) at the $k^{th}$ timestep as a function of some state $\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathcal{X}_{D}$. The idea of the above formulation is we compute a cost at some terminal time, $t_{N}$, using the cost function $g_{N}(\cdot)$, and then work backwards in time recursively to gradually obtain the optimal policy for the problem at each timestep. With the mathematical formulation resolved, the next step is to put all of this into an algorithm!

The Algorithm

The algorithm can be defined in pseudocode using the following:

Initialize Optimal Cost-To-Go and Optimal Policy

init $V_{i}^{*}(x) = \infty$ $\forall x \in \mathcal{X}_D, \forall i \in \lbrace 1, \cdots, N\rbrace$

init $\mu_{i}^{*}(x) = 0$ $\forall x \in \mathcal{X}_D, \forall i \in \lbrace 1, \cdots, N-1\rbrace$

Compute policy by working backwards in time

- $x \in \mathcal{X}_D$

- $i = N$

- $V_i^{*}(x) = g_{N}(x)$

- init $\hat{V} = 0$

-

$u \in \mathcal{U}_D$

- $\hat{V} = g_{i}(x,u) + V_{i+1}^{*}\left(f(x,u)\right)$

-

$\hat{V} < V_{i}^{*}(x)$

- $V_{i}^{*}(x) = \hat{V}$

- $\mu_{i}^{*}(x) = u$

With the algorithm defined above, one can translate this into a code and apply it to some interesting problems! I have written a code in C++ to implement the above algorithm, which can be found at my Github. Assuming one has written the algorithm written above, the next step is to try it out on solving some control problems! Let's take a look at an example.

Nonlinear Pendulum Control

Problem Statement

The Nonlinear Pendulum control problem is one classically considered in most introductory control classes. The full nonlinear problem can be formulated with a nonlinear Second-Order Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) in the following manner:

\begin{align} \ddot{\theta}(t) + c \dot{\theta}(t) + \kappa \sin\left(\theta(t)\right) &= u \\ \theta(t_0) &= \theta_{0} \\ \dot{\theta}(t_0) &= \dot{\theta}_{0} \end{align}where $u$ is a torque the controller can apply, and $c,\kappa$ are constants based on the exact pendulum system configuration. For this particular problem, we are going to try and build a controller that can invert the pendulum. Additionally, we are going to constrain the values for $u$ such that it is too weak to directly lift the pendulum up to an inverted position. The constraint is to, at least, make $|u| \lt \kappa$, ensuring it needs to find some different strategy to get the pendulum to an inverted position. Given we now have this problem statement, let's make this problem solvable using the Approximate Dynamic Programming approach shown earlier!

Conversion to Dynamic Programming Formulation

First and formost, we should take the dynamical system in the problem statement and convert it into the discrete dynamic equation Dynamic Programming requires. Our first step is to pose this problem as a system of First-Order differential equations in the following way:

\begin{align} \dot{x_1} &= x_2 \\ \dot{x_2} &= u \; - c x_2 \; - \kappa \sin( x_1 ) \\ &\text{or} \nonumber \\ \dot{\boldsymbol{x}} &= F(\boldsymbol{x},u) \end{align}where $\lbrack \theta,\dot{\theta}\rbrack ^{T} = \lbrack x_1,x_2\rbrack^{T} = \boldsymbol{x}$. We can then discretize this dynamical system, using Finite Differences, into one that can be used in Dynamic Programming. This is done using the below steps:

\begin{align} \dot{\boldsymbol{x}} &= F(\boldsymbol{x},u) \nonumber \\ \frac{\boldsymbol{x}_{k+1} - \boldsymbol{x}_{k}}{\Delta t} &\approx F(\boldsymbol{x}_{k},u_k) \nonumber \\ \boldsymbol{x}_{k+1} &= \boldsymbol{x}_{k} + \Delta t F(\boldsymbol{x}_{k},u_k) \nonumber \\ \boldsymbol{x}_{k+1} &= f(\boldsymbol{x}_{k},u_k) \end{align}where $f(\cdot,\cdot)$ becomes the discrete dynamical map that is used within the Dynamic Programming formulation. Now the next step is to define our discrete State and Control sets, $\mathcal{X}_{D}$ and $\mathcal{U}_{D}$ respectively, that will be used. These sets will be defined as the following for this problem:

\begin{align} \mathcal{X}_{D} &= L(\theta_{min},\theta_{max},N_{\theta}) \bigtimes L(\dot{\theta}_{min},\dot{\theta}_{max},N_{\dot{\theta}}) \\ \mathcal{U}_{D} &= L(-u_{max},u_{max},N_{u}) \end{align}where $\theta_{min},\theta_{max},\dot{\theta}_{min},\dot{\theta}_{max},u_{max}, N_{\theta},N_{\dot{\theta}},N_{u}$ will have exact values assigned based on the specific pendulum problem being solved. The last items needed to make this problem well posed is the cost functions needed to penalize different possible trajectories. For this problem, we will used the cost functions defined below:

\begin{align} g_{N}(\boldsymbol{q}) = g_{N}(\theta,\dot{\theta}) &= Q_{f} (|\theta|-\pi)^2 + \dot{\theta}^2\\ g_{k}(\boldsymbol{q},u) = g_{k}(\theta,\dot{\theta},u) &= Q (|\theta|-\pi)^2 + Ru^2 \end{align}where $g_{k}(\cdot,\cdot)$ is defined $\forall k \in \lbrace 1, 2, \cdots, N-1 \rbrace$ and $R, Q, Q_f$ are scalar weighting factors that can be defined depending on how smooth you want the control to be and how quickly you want the pendulum to become inverted. Now that all the items are defined so Dynamic Programming can be used, let's solve this problem and see what we get!

Solution using Approximate Dynamic Programming

Based on the Dynamic Programming formulation above of the Nonlinear Pendulum Control problem, we can crank out an optimal controller (at each timestep) algorithmically. To test the approach, algorithms I wrote that can be found at my Github are using the following values for the parameters mentioned earlier:

\begin{align*} N &= 80 \\ c &= 0.0 \\ \kappa &= 5.0 \\ \theta_{min} &= -\pi \\ \theta_{max} &= \pi \\ N_{\theta} &= 3000\\ \dot{\theta}_{min} &= -3 \pi \\ \dot{\theta}_{max} &= 3 \pi \\ N_{\dot{\theta}} &= 3000 \\ u_{max} &= 1.0 \\ N_{u} &= 5 \\ R &= 0 \\ Q &= 10 \\ Q_f &= 100 \end{align*}Note that in the discrete dynamics, due to the discontinuity of the angle $\theta$ at $\theta = -\pi$ and $\theta = \pi$, the discrete dynamics actually need to be modified for the equation updating $\theta$ at each timestep. This equation can be updated to the following:

\begin{align} \theta_{k+1} = B( \theta_{k} + \Delta t \dot{\theta}_{k} ) \end{align}where $B(\theta)$ bounds the input angle $\theta$ to be between $-\pi$ and $\pi$ and is defined as the following:

\begin{align} B(\theta) = \begin{cases} \theta \,- 2\pi & \text{if } \theta \gt \pi \\ \theta + 2\pi & \text{if } \theta \lt -\pi \\ \theta & \text{Otherwise} \end{cases} \end{align}Given we use the modified dynamics for the pendulum, we can use the Approximate Dynamic Programming algorithm described earlier to produce an optimal controller shown below. Note that this controller is actually just the optimal controller found for the first timestep. However, since the cost function penalizes the pendulum for not being inverted throughout its whole trajectory, the controllers made via Dynamic Programming are actually individually capable of inverting and stabilizing the pendulum. Thus, one only really needs one of these optimal controllers to get the desired result.

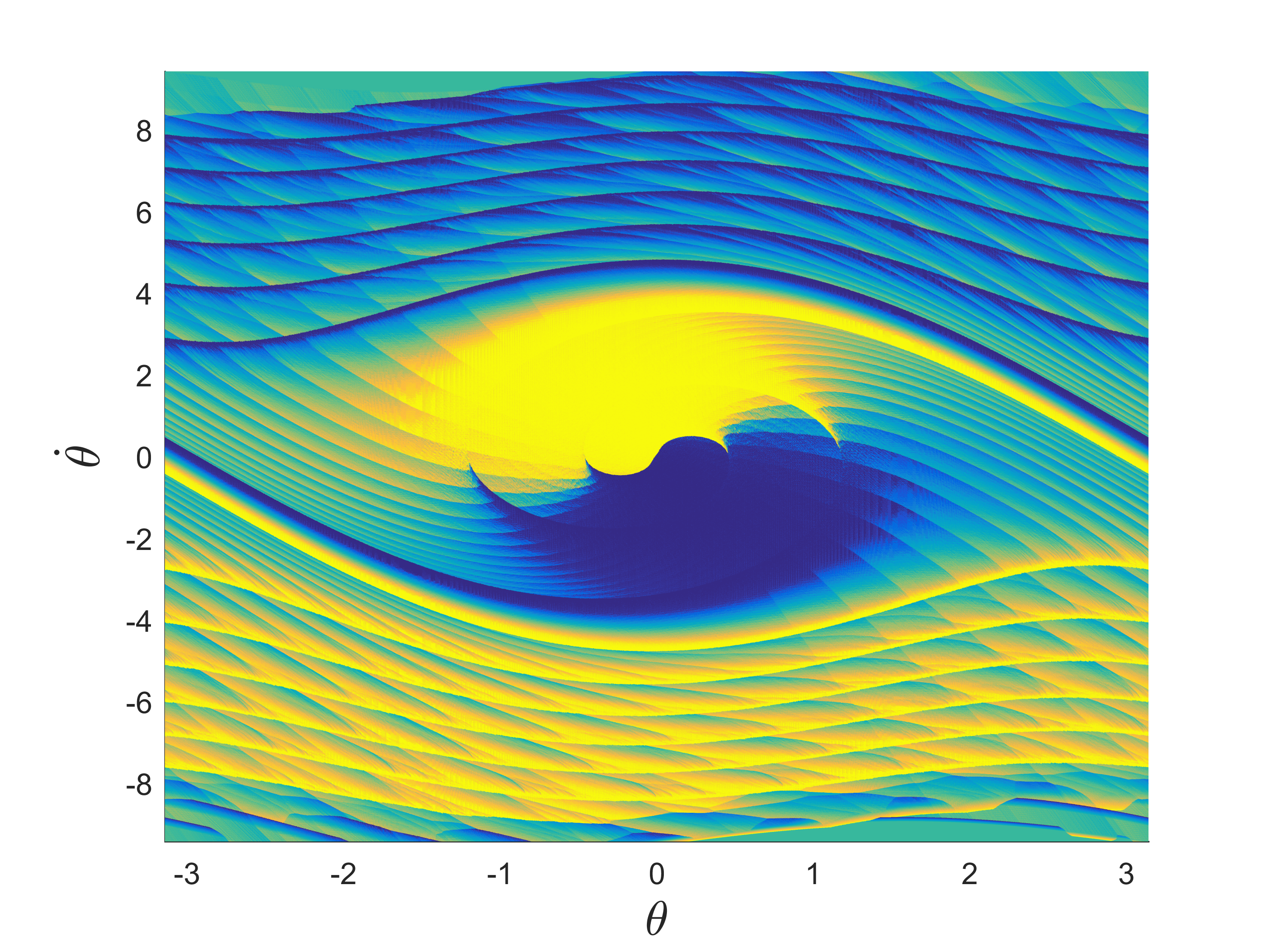

The graphic below shows the value the controller produces for any given $\theta$ and $\dot{\theta}$ within $\mathcal{X}_{D}$. Yellow is a positive torque value for $u$, while blue is a negative torque value for $u$.

As we can see in the graphic above, the optimal controller produced using Dynamic Programming is extremely nonlinear. Looking at the result, it would be hard to think of a great way to even represent this controller using a finite approximation with some set of basis functions.

The result is also interesting due to the complexity of the controller and patterns produced for various values for $\theta$ and $\dot{\theta}$. While there is certainly analysis that could be done to further understand what the optimal controller is doing, it would probably just be better to get a glimpse at what this policy actually does via visualization. Below is a video showing how it performs!

Shortcomings of Algorithm

Now while the above algorithm has proven to produce some pretty awesome results, the practicality of the algorithm as-is is pretty small. For starters, the amount of space needed for storing the complete controller at each timestep is on the order of $O( N |\mathcal{X}_{D}| )$, while the algorithmic computation is on the order of $O(N |\mathcal{X}_{D}| |\mathcal{U}_{D}| )$. For low dimensional problems, this may not seem like a big deal, but both $|\mathcal{X}_{D}|$ and $|\mathcal{U}_{D}|$ blow up as dimensions increase due to the Curse of Dimensionality.

For example, given equations from the definitions section, we can compute the cardinality of $\mathcal{X}_{D}$ and $\mathcal{U}_{D}$ to be the following:

\begin{align} |\mathcal{X}_{D}| &= \prod_{i=1}^{n} N_{i} \\ |\mathcal{U}_{D}| &= \prod_{i=1}^{m} M_{i} \end{align}These cardinality results show that each dimension we add multiplies the size of the State and Control spaces, in turn making the values of $|\mathcal{X}_{D}|$ and $|\mathcal{U}_{D}|$ potentially huge! For example, if all we did was model a rocket in 3D, the state is 12 dimensions (or 13 if you use quaternions). Chopping up each dimension into just $10$ discrete pieces would make $|\mathcal{X}_{D}| = 10^{12}$ ... which is way too huge a number to use practically, and $10$ discrete pieces per dimension is not even a lot! So even without looking at any discretized control space, this Approximate Dynamic Programming method proves impractical for a realistic problem.

Conclusion

Within this post, we saw a way to use Dynamic Programming and approximately tackle deterministic control problems... no matter how nonlinear the dynamics or cost functions are! We saw the algorithm described used to find a nonlinear optimal controller for a Nonlinear Pendulum and invert the pendulum. We also saw how impractical this method, as-is, can be for realistic problems of larger dimensionality.

While the dimensionality does become a problem for a variety of problems, there are fortunately still some problems that can be adequately solved using the above approach. For those looking for something more capable, those interested can investigate other Approximate Dynamic Programming techniques in the literature. Some related areas of potential interest is that of Reinforcement Learning, as these areas are attempting to solve the same problem but with more flexibility than traditional Dynamic Programming.